If music theory seems like chunks and pieces of stuff that don’t relate, you are in the right place. Fortunately, music theory is extremely logical and organized. Once you get the basics, it just gets more and more fun as you build into more advanced concepts.

We briefly touched on diatonic major scales in our last blog – now we will dive in and get a clear understanding of what is really happening. Again, music is based on the first seven letters of the alphabet:

A B C D E F G A

When we get to G, it just starts all over again an octave higher with the same alphabetical names – so, starting on A we proceed up the alphabet to G, then the next note is A (an octave higher), and this just repeats on your instrument until you run out of notes.

We can start on any note: C D E F G A B C

As previously discussed, there are only two spots in music where natural half-steps occur: B to C and E to F. Otherwise, the other spaces are a full-step apart (2 half-steps).

Diatonic Scale Structure

It just so happens that when we start on C, the structure and sound is a diatonic major scale – in fact, the key of C is the only key where this occurs “naturally” – meaning no sharps (#) or flats (b) are required – all seven notes are naturals.

There is a specific pattern or “structure” in the spaces of a diatonic major scale. Remember, the pattern of a chromatic scale? It is based on all half-steps – it is semetrical, consistant, and a bit redundant to play or listen to – on guitar you start on any string and just play every fret in a row up the neck. However, to play a diatonic scale we need to play a specific pattern of notes, or frets if you’re a guitarist – in other words, instead of playing every fret, we skip one every once in a while:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

C D E F G A B C

1 1 ½ 1 1 1 ½ = diatonic major scale structure

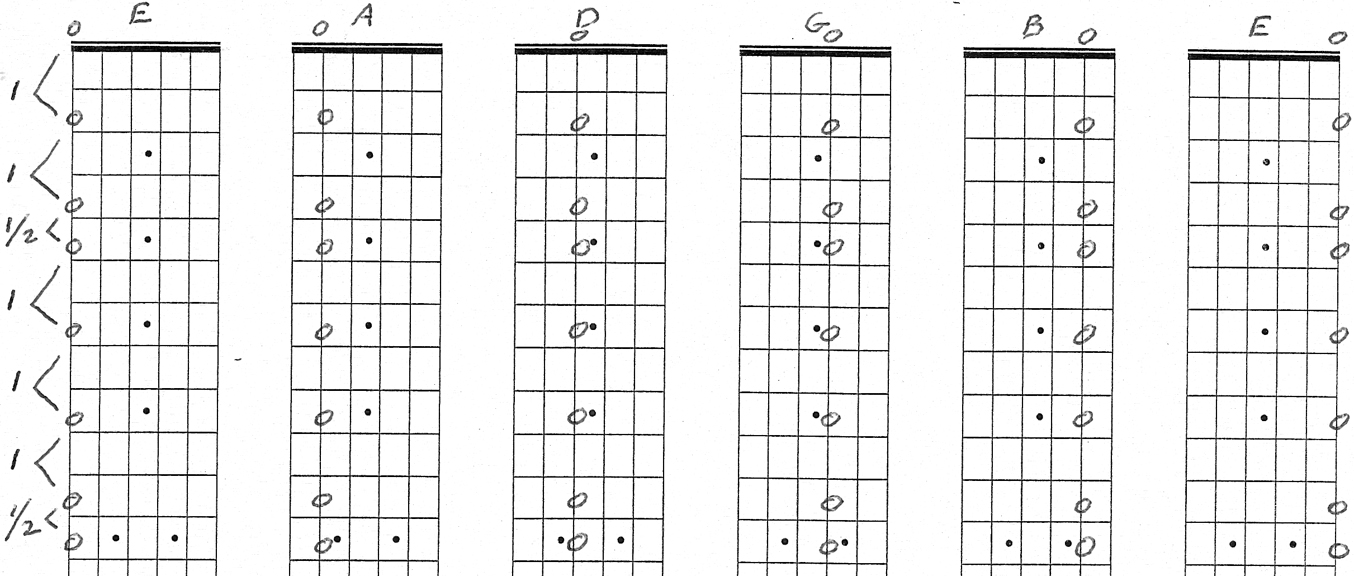

As you can see, the structure for a diatonic major scale is 1 1 ½ 1 1 1 ½ , i.e. whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half. This structure is the same for all twelve keys. On the guitar, you could start on any open string, play this pattern, and you are playing a diatonic major scale:

In our next blog, this topic will be expanded to cover all twelve keys, but suffice to say, since C is the only key that results in a natural diatonic scale, the other eleven keys will require either sharps or flats ( # or b) to adjust the spaces to fit the diatonic major scale pattern. Meanwhile, if you are a guitarist, practice this pattern on each string, keeping in mind that the name of the key you are playing is simply the name of the string – so now that you know this pattern, you know how to play 5 scales on the guitar (the top and bottom strings being both E).

Until next time, have fun burning it up!

Musically yours,

Al

by Al Dinardi

22 Apr 2015 at 09:18

Chromatic scales are symmetrical in comparison to diatonic scales which have irregular spaces (half steps mixed with whole steps). The first half of a chromatic scale is identical to the last half (6 half steps each) – and every degree of the chromatic scale is identical (all half steps)

by Alton

11 Mar 2015 at 18:09

You lost me at semmetrical., thats a new one for me.

by Al Dinardi

27 Jan 2010 at 20:33

The purpose of the “cool” sketches was to provide a visual picture of the space pattern between notes in a diatonic scale – showing that regardless of which key or note you begin on, every diatonic scale uses that same pattern. If you begin on the low E string, you are playing an E diatonic scale. If you begin on the A string, you are playing an A scale, and so on. It is the “pattern” and not the notes that determine the “type” of scale – whereas note names determine the “name” of the scale.

The dots or block inlays on guitar necks serve a different purpose which we will discuss in a later blog.

by Doug Ross

27 Jan 2010 at 11:52

Why are the dots on a guitar neck placed where they are, instead of the way you show on your cool scetches here?