One of life’s injustices: you don’t get to choose your relatives! As in life, music comes with relatives. Every major chord has a relative minor – or you could say every minor chord has a relative major. Likewise, scales have relatives as well. In fact, entire keys have relatives! There’s no escaping them – they’re everywhere!

You’ve no doubt heard the term relative minor, and perhaps have always wanted to know exactly what it means. Here it is: relative minor scales begin on the sixth degree of major scales. That’s it? That’s it. Not exactly life changing – nor is it rocket science. Here it is applied to the key of C:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 C D E F G A B C D E F G A

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

In this case, A minor is the relative of C major. The important things to notice here:

Both scales share the same key signature

The relative minor begins on the 6th degree

The scale structures are different, since the half-step / whole-step pattern is skewed.

Here it is in the key of G:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 G A B C D E F# G = G major

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

E F# G A B C D E = E minor

Let’s look at this backwards, starting with a minor scale first, then find the relative major scale:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 A B C D E F G A = A minor

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

C D E F G A B C = C major

In this case, the relative major is a minor 3rd above the minor scale.

Remembering that major 6th inverts to minor 3rd (see Intervals: The Space Time Continuum of Music ) it makes sense. In other words, going up a major 6th is the same thing as coming down a minor 3rd.

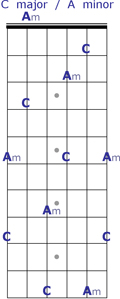

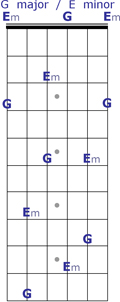

Knowing this, it is easier to think of relative minor and major being just a minor 3rd apart – always visualizing the relative minor key / scales just a minor 3rd down from wherever you’re playing. On guitar – that’s just three frets below and super easy to visualize, using the two-fingering method discussed in Guitar Fingerboard Basics: Part I:

Notice the repetitive patterns discussed earlier in Fingerboard Basics. Finding relative minor scales is simply a matter of dropping down 3 frets, then play the major scale beginning from that point. We will cover this in more detail in an upcoming post that covers all major scale fingerings on the guitar.

Meanwhile, here is a hint: all scales, major or minor, are played with only two fingerings! In fact, as I’ve previously hinted in other posts, everything on guitar can be viewed as having only two fingerings – all chords, scales, arpeggios, melodies, songs, entire arrangements – I mean everything! In my view, there is no such thing as the “five fingering method for scales on the guitar” – or “seven fingering method for scales and arpeggios” – or “5,000 chords for the guitar“. As you will see, it is really much simpler than that – and the more simpler you can visualize it, the more you can focus on making music instead of worrying about memorizing fingerings.

Below are the nine most common keys with their relative minor key counterparts:

Key Sig Major Minor

C C Ami

G # G Emi

D ## D Bmi

A ### A F#mi

E #### E C#mi

F b F Dmi

Bb bb Bb Gmi

Eb bbb Eb Cmi

Ab bbbb Ab Fmi

No need to actually memorize this, since it is so simple to find the relative keys. However, once you begin performing music with this understanding of relative major / minor, you can’t help but think of them together. When faced with playing a song in E minor for example, my brain automatically thinks G major – I seem to no longer have any say in the thought process – to me E minor and G major are one in the same – and in actuality, they are!

This is especially useful for playing Pentatonic scales – such as found in blues, rock, country, and jazz styles of music. The bluesy sounding Pentatonic minor scale is related to the more pop or country sounding Pentatonic major scale – with many songs utilizing both sounds within the same arrangement. All that fun lies ahead when we start tackling scales and modes.

In summary: Every major key has a corresponding relative minor key – and in fact they are both the same key. The same is true for all major chords, scales, and arpeggios. The relative minor is a major 6th above – or more easily visualized by looking a minor 3rd down. Likewise, when playing in minor keys, the relative major is a minor 3rd above – on guitar that’s just three frets away – right under your finger tips!

Practice starting on any note and see how quickly you can find the relative minor root – refer to the guitar charts above. If you already know your scales, start from there and play the minor scale. Do the same in reverse. As always, do it all over the fingerboard – better to know one thing ten different ways, than ten things only one way.

If you don’t know your scales – fear not, they are easy – and are coming to a post in the near future. Until then, I remain –

Musically yours,

Al Dinardi

by Al Dinardi

02 May 2010 at 22:31

Your ear and personal musical taste is what music is all about – and should always come first and foremost. Music theory is simply a language – no more, no less. A way to attempt to understand, communicate, and educate music to others. It is a tool that is available to be harnessed – with the potential to inspire new avenues for musical creation and growth.

I appreciate your input and tenacity. It is not necessary to grasp 100% of everything you read here – my hope is that every now and then you might find one or two gems of inspiration that could contribute to your musical endeavors and enjoyment – if that happens, and I believe it will, it will all have been worth it.

by Doug Ross

27 Apr 2010 at 06:36

Al, I appreciate all of this wonderful work you are doing but I think I’m gonna stick to my parallel diatonic scales. I may be limited in some ways with that, but at least I still have the freedom of chess. I will continue to enjoy these posts and reading the comments and questions. I have found that if I just stick to what sounds good, it must be o.k. The creative process at least for myself is like a light bulb being turned on. Who knows!…….maybe there is a fully chromatic light bulb coming my way and I just don’t know it yet.